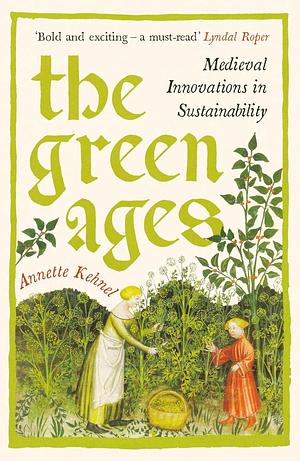

The Green Ages: Medieval Innovations in Sustainability

Genres: History,

Non-fiction Pages: 352

Rating:

Synopsis: Fishing quotas on Lake Constance. Common lands in the UK. The medieval answer to Depop in the middle of Frankfurt.

These are all just some of the sustainability initiatives from the Middle Ages that Annette Kehnel illuminates in her astounding new book, The Green Ages. From the mythical-sounding City of Ladies and their garden economy to early microcredit banks and rent-a-cow schemes, Kehnel uncovers a world at odds with what we might think of as the typical medieval existence.

Pre-modern history is full of inspiring examples and concepts that open up new horizons. And we urgently need them as today's challenges - finite resources, the twilight of consumerism, growing inequality - threaten what we have come to think of as a modern way of living sustainably.

This is a revelatory look at the past that has the power to change our future.

Annette Kehnel’s The Green Ages is trying to offer a way forward for society based on examples of the past — not necessarily saying they’re fully transferrable, or that everyone can simply swear themselves to eternal poverty, or anything like that, but to show that there are ways forward that aren’t endless profit. That “progress” doesn’t have to look like this. I admire the sentiment, and I even agree that some aspects of the past are worth re-examining and potentially emulating, or at least adapted.

That said, her examples are either deeply naive or very disingenuous, or a mixture of both. For example, to promote communal, self-sufficient living, she uses the examples of the Benedictines and the Cistercians — which famously became extremely wealthy, at the very least, if not outright exploitative. She says the sale of indulgences was an early form of crowdfunding, and I think this quotation is a good one to show how weird her interpretations are:

Indulgences worked roughly like modern crowdfunding initiatives, with all the attendant opportunities as well as risks. They were used to finance major infrastructure and creative projects, and sustained some of the most important Renaissance artsists, from Raphael to Michelangelo. Yet they also show that the crowd’s patience can eventually run out, and were a major trigger factor for the Reformation.

This is just… bizarre.

In the end, where I have my own understanding of a subject, I can tell that she’s completely misunderstanding the past. I can’t evaluate all of her examples for myself, but based on what I can evaluate, I trust none of it.

It’s a nice idea for a book, but it just… doesn’t hold up to the most cursory critique (because believe me, my grasp on history is often tenuous where it doesn’t directly intersect my literary knowledge).

Rating: 1/5 (“didn’t like it”)