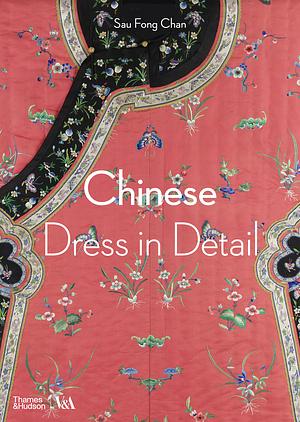

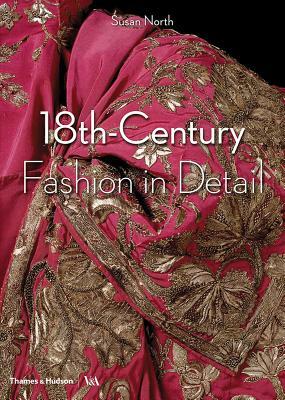

18th-Century Fashion in Detail

by Susan North

Genres: Fashion, HistoryPages: 224

Series: Fashion in Detail

Rating:

Synopsis:This beautifully illustrated book reveals sharp pleats, high collars, gleaming pastes, colorful beads, elaborate buttons, and intricate lacework that make up some of the garments in the Victoria and Albert Museum's extensive fashion collection. With an authoritative text, exquisite color photography of garment details, and line drawings and photographs showing the complete construction of each piece, the reader has the unique opportunity to examine up close historical clothing that is often too fragile to be on display. It is an inspirational resource for students, collectors, designers, and anyone who is fascinated by fashion and costume.

The V&A’s 18th-Century Fashion in Detail is written by Susan North, and it’s a beautiful item, with glossy full-colour images of details from the garments discussed. My main quibble is that it doesn’t provide full images of how the garments looked as a whole, rather breaking them down into one bit that the author has chosen to discuss, like just a close-up of some embroidery. There are sketches showing the garments and how they’re put together, but it’s not really the same.

It’s still a fascinating read, especially when it discusses some of the unfinished garments that were sold part-completed, so they could be fitted to the wearer. There’s almost nothing about children’s clothes, which made me curious — I think in this period they were still usually mini-versions of the adult clothing, but I’d still like to see some examples.

It’s a lovely volume, despite the caveats.

Rating: 4/5 (“really liked it”)