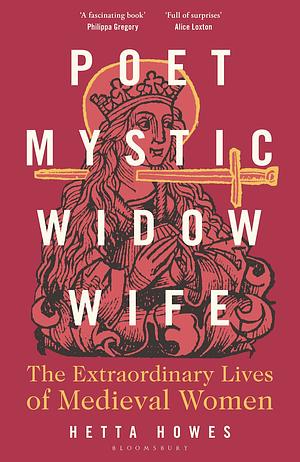

Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife: The Extraordinary Lives of Medieval Women

by Hetta Howes

Genres: History, Non-fictionPages: 298

Rating:

Synopsis:What was life really like for women in the medieval period? How did they think about sex, death and God? Could they live independent lives? And how can we hear their stories?

Few women had the luxury of writing down their thoughts and feelings during medieval times. But remarkably, there are at least four extraordinary women who did. Marie de France, a poet; Julian of Norwich, a mystic and anchoress; Christine de Pizan, a widow and court writer; and Margery Kempe, a "no-good wife". In their own ways these four very different writers pushed back against the misogyny of the period. Each broke new ground in women's writing and left us incredible insights into the world of medieval life and politics.

Hetta Howes has spent her working life uncovering these women's stories to give us a valuable and unique historical biography of their lives that challenges what we think we know about medieval women in Europe. Women did earn money, they could live independent lives, and they thought, loved, fought and suffered just as we do today.

This mesmerizing book is an unforgettably lively and immersive journey into the everyday lives of medieval women through the stories of these four iconic women writers, some of which are retold here for general readers for the first time.

Hetta Howes’ Poet Mystic Widow Wife does a pretty good job at discussing the lives of medieval women in general, while reflecting specifically on Marie de France, Christine de Pizan, Margery Kempe and Julian of Norwich. If considered as intending to shed light on those lives specifically, it feels pretty disorganised and lacks detail on Marie de France and Julian of Norwich — which is in part due to lack of sources and in part due to choosing poorly (though there may not be many good choices).

Overall, it didn’t quite work for me. I think it was the general feeling of it not being super organised, for a start; each section would jump around slightly in time and place, trying to touch on the four women regularly, but not always managing to link them in to the chapter’s themes very well.

Perhaps it’s partly a matter of style; while Howes’ style is readable, I didn’t love it. Her sources are pretty sparse, and overall this might all be explained by the fact that she’s qualified in medieval literature (which probably informed her choice of sources) rather than history. Literature was my first field of study as well and one in which she’s more qualified than I am, and medieval literature in particular has an overlap with understanding medieval history… but it’s not the same. I know a lot about the role of medieval women through that same literary lense, and maybe I was hoping for something a bit more rooted in named sources. I was also hoping for more about Marie de France, whose works I studied (in translation).

In any case, if you’re looking for an accessible, chatty sort of popular history, with reimaginings about what Margery Kemp and Christine de Pizan thought and felt, this might be more up your street. If you’re here for Marie de France or Julian of Norwich, perhaps not.

Rating: 2/5