This morning, I woke up at five AM because I needed a drink. I found a note on the floor from my sister, telling me how heartbroken she was about recent developments in The 100, which she’d excitedly stayed up to watch via a stream. For weeks she’s been telling me about this show: Clarke and Lexa this, Clarke and Lexa that, the team promise good queer representation, etc, etc. She was happy and hopeful and it was nice.

In last night’s show, they killed the lesbian. (And as I said on Twitter the first time, if you’re annoyed about the spoiler, cry yourself a river and use it to get in the sea.)

Me and my sister are both queer. We both attended a conservative little private school where we were, as far as I can tell, the first kids to be openly gay while at school since it was founded in the 17th century. You better believe we received threats and constant harassment, from the moment we got onto the school bus in the morning to the moment we got off it at night — and sometimes longer, since people realised it’d be fun to start calling my sister up to continue with it.

In case you hadn’t noticed, homophobia is definitely not dead. I’m 26 and my sister is 21, and mostly things have got better for us. But you can bet we haven’t forgotten it, and that every time I think I see someone from my old school, I still feel a frisson of fear.

But we’re talking about fiction, right? Doesn’t harm anything.

It used to be a rule: if you have a lesbian character, they have to either go straight or come to a tragic end. Queer Tragedy. It had to be there: queer people don’t get to be happy (because they’re deviant). The Well of Loneliness counts as great queer literature — you can tell from the title it’s not going to be happy, and I can assure you it isn’t. It ends with the queer couple breaking up, and one partner going off to be part of a straight relationship, because that’s “safer”.

So no, your decision is not “bold“, Jason Rothenberg. It’s not narratively necessary, because you write the fucking narrative. You can choose. And you chose to look at the excitement around the queer representation on your show, the whole fandom climate with people shouting that a queer character should die so they could have their straight ship, the sheer bubbling hope that maybe this time, maybe this time, people would finally have a lesbian heroine who can kick ass and save everyone and be with the person she loves.

And you chose to say no.

Let me emphasise this: it was not forced upon you. You could’ve made a whole new narrative.

Instead, you killed the lesbian and my sister cried for over an hour. Not just because it was sad, not just because she’d got invested, but because she’d hoped that this time it’d be different and she’d get a love story written for her.

Now I’ve already seen the excuses.

- It was necessary for the narrative. Covered this one. Next?

- Lots of characters die. And? It still means something each time. And this time it filled a shitty, shitty trope.

- The actor had to leave anyway. And character death is the only way to leave the show?

- It was heroic. Heroic don’t keep anyone warm at night.

- The show never mentions discrimination by sexuality. It doesn’t have to. We live in a world where that exists, and we experience the story framed by our world.

- You should be grateful for what you’ve got. When what we’ve got is a reaffirmation of a shitty outdated narrative, why should we be?

When you kill a queer character, you’re killing a disproportionate amount of our on-screen representation. Sure, the diversity was there for a moment, but now the list of queer characters on TV is shorter by one. And it wasn’t that long to begin with. And these are people who need to see themselves in the world, who need to be treated as if they matter. Queer youth have ridiculously high suicide rates compared to their straight peers. You’re much, much more likely to get kicked out by your parents for being gay than for being straight. Schools turn a blind eye. People actively try and tell you that you’re evil and you’ll come to a bad end.

The 100 chose the easy option. The well-trodden path. It doesn’t matter if the lesbian had a heroic end. It doesn’t matter if her death furthers the plot, or even if her partner goes on to do great things without her. The key thing is: without her. The key thing is: queer people die.

We do. Every day. And it’s high time that stopped being our only story.

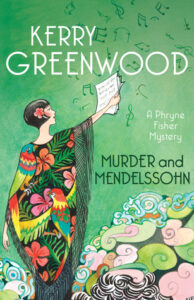

Murder and Mendelssohn, Kerry Greenwood

Murder and Mendelssohn, Kerry Greenwood