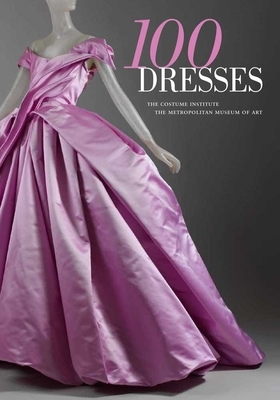

100 Dresses

by The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Genres: Fashion, History, Non-fictionPages: 232

Rating:

Synopsis:An irresistible look into more than 300 years of fashion through an exquisite collection of designer dresses

What woman can resist imagining herself in a beautiful designer dress? Here, for the first time ever, are 100 fabulous gowns from the permanent collection of the renowned Costume Institute at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, each of which is a reminder of the ways fashion reflects the broader culture that created it.

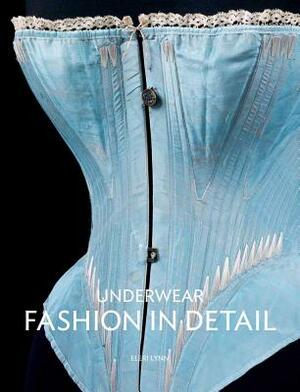

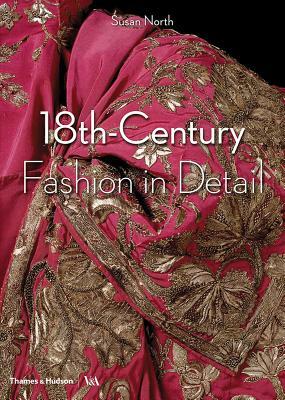

Featuring designs by Paul Poiret, Coco Chanel, Madame Gr s, Yves Saint Laurent, Gianni Versace, Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen, and many others, this one-of-a-kind collection presents a stunning variety of garments. Ranging from the buttoned-up gowns of the late 17th century to the cutting-edge designs of the early 21st, the dresses reflect the sensibilities and excesses of each era while providing a vivid picture of how styles have changed--sometimes radically--over the years. A late 1600s wool dress with a surprising splash of silver thread; a large-bustled red satin dress from the 1800s; a short, shimmery 1920s dancing dress; a glamorous 1950s cocktail dress; and a 1960s minidress--each tells a story about its period and serves as a testament to the enduring ingenuity of the fashion designer's art.

Images of the dresses are accompanied by informative text and enhanced by close-up details as well as runway photos, fashion plates, works of art, and portraits of designers. A glossary of related terms is also included.

100 Dresses is a very shallow overview of some of the dresses held by The Costume Institute at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and as such is obviously a very narrow selection. It’s heavy on some individual designers (like Dior) and surprisingly light on others (Vionnet), and it’s not like there’s a lot of details about any given dress or designer, but it’s still a fun quick read.

Despite the short blurbs for each dress, there are some fascinating details — I particularly boggled at the dress with probably hundreds of pleats, pressed rather than stitched into place, which would need to be returned to the designer for the pleats to be re-set if it got damp or just crushed with wear.

Not exactly a groundbreaking volume, but enjoyable.

Rating: 3/5 (“liked it”)