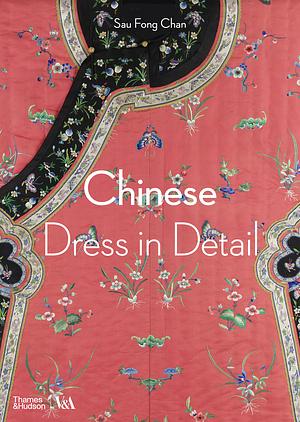

Chinese Dress in Detail

by Sau Fong Chan

Genres: History, Non-fictionPages: 224

Rating:

Synopsis:Chinese Dress in Detail reveals the beauty and variety of Chinese dress for women, men, and children, both historically and geographically, showcasing the intricacy of decorative embroidery and rich use of materials and weaving and dyeing techniques. The reader is granted a unique opportunity to examine historical clothing that is often too fragile to display, from quivering hair ornaments, stunning silk jackets and coats, festive robes, and pleated skirts, to pieces embellished with rare materials such as peacock-feather threads or created through unique craft skills, as well as handpicked contemporary designs.

A general introduction provides an essential overview of the history of Chinese dress, plotting key developments in style, design, and mode of dress, and the traditional importance of clothing as social signifier, followed by eight thematic chapters that examine Chinese dress in exquisite detail from head to toe. Each garment is accompanied by a short text and detail photography; front-and-back line drawings are provided for key items.

An extraordinary exploration of the splendor and complexity of Chinese garments and accessories, Chinese Dress in Detail will delight all followers of fashion, costume, and textiles.

The V&A’s Chinese Dress in Detail, written by Sau Fong Chan, is a gorgeous physical item with glossy pages full of colour photographs, displaying both close-ups and zoomed out images that give you an idea of what the full garment looks like, and accompanied by sketches of how the garments are put together, and at times with useful context like illustrations from the period.

The book has a useful introduction setting the scene, and then each garment has its own little description/discussion section. Most of the garments get a full double-page spread. It’s only a sampling, inevitably, but Sau Fong Chan has selected garments that represent different ethnic groups within China like the Uyghurs and the Miao, and tries to be clear about how diverse “Chinese” fashion can be.

It was fascinating and beautiful, and I recommend it if you have an interest!

Rating: 5/5 (“it was amazing”)